The Brothers Ely - Martin

The Long Shadow of Cain

In the quiet corners of South East England, where memory drapes itself over the hedgerows and old stone walls, the story of the Ely family unfolded—not in a grand castle or a noble estate, but in the shifting sands of loyalty, greed, and fractured love. Theirs was a tale that might have pleased the old Russian masters or the California realists, for it carried within it all the notes of virtue betrayed, envy cultivated, and the slow poison of regret. Some betrayals happen in a sudden blaze — a door slammed, a blade drawn, a trust shattered in an instant. Others are slower, quieter things, like ivy creeping over the bricks of a house, wrapping every corner until the structure is choked and dying. The story of Dennis Ely’s children was of the second kind — years in the making, meticulously planned, an old human pattern repeating itself in new clothes.

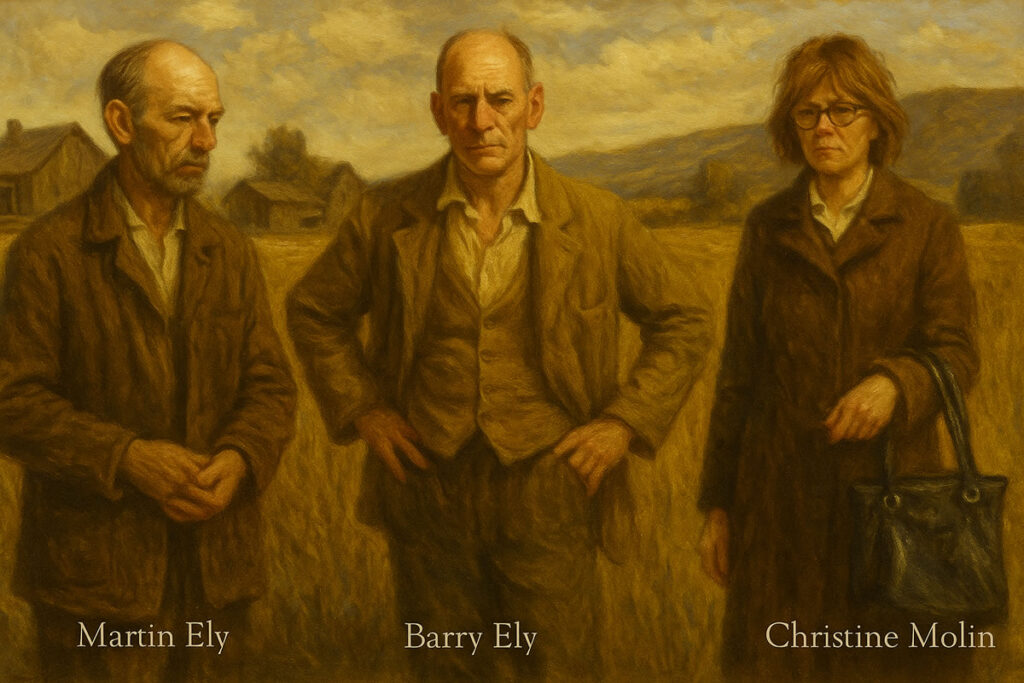

Dennis Ely was a flawed man and no stranger to loss. He had been, in his younger days, a man with a quick wit and a steady hand, a flawed man for sure but none the less, a father to Barry, Martin, and Chris through his beloved wife, Jeannie.

Barry wasn’t blessed with good looks, and as Dennis once put it with a sigh, “Barry is no oil painting.” Martin, the second-born, had always possessed a sly and cunning intellect, a planner by nature, a man who understood the long game. Chris, the youngest of the three, eventually made her life across the Atlantic, in America.

Jeannie was the light in the family’s kitchen, the warmth in the evenings, the tether holding Dennis steady. And then, at fifty-two, she was gone. Death does not politely knock before entering; it storms in and leaves the survivors stunned. Dennis never fully recovered from that strike. In the years that followed, he drifted. He missed the small daily anchors Jeannie had given him, and he missed her way of smoothing over the frictions between him and his children. Without her, the family did not quite hold. Barry and Martin began to pull away from him.

Then there was Christine, Dennis’s daughter from an earlier relationship with a Danish woman. As a toddler, she had been abandoned along with her mother when Dennis built a new life with Jeannie and had his children, Barry, Martin, and Chris. This abandonment had calcified into a deep bitterness, a constant ache of being the outsider, the one who was not fully part of the English family. She carried a quiet resentment towards Barry, Martin, and especially Chris, seeing in their shared parentage with Jeannie a bond and a belonging that had been denied to her.

The Seed of the Plan is a subtle thing. It is tempting to believe that betrayal begins at a single point — the first lie told, the first selfish thought entertained. But more often it starts with a seed, and that seed is watered by opportunity. For Martin, the opportunity lay in his father’s will. Dennis had spoken of his estate in vague terms over the years. There were Arkansas properties that needed tending, a detail Chris, living in America, had taken some responsibility for managing from afar. There was money, scattered investments, the usual mix of assets and loose ends.

Martin understood that the executor of the will would have immense influence over how those things played out. And so he began, subtly at first, to position himself as the logical choice. Martin, in his capacity as the “dutiful” son, even billed Dennis £2,500 for the time he spent helping him while he was ailing—a cold, calculated transaction that demonstrated his true motivations were never rooted in affection. We will never know all the conversations that led to Dennis naming Martin sole executor, but we do know this: it was no last-minute accident. It was the product of years of careful cultivation. Martin became indispensable — the one who would handle things, the one who “could be trusted” with the details. He would visit Dennis, not with overt displays of affection, but with an air of competence and practicality, subtly undermining Barry’s more self-absorbed nature and Christine’s perceived distance due to her Danish heritage. In January 2017, in the quiet of an unremarkable day, Dennis signed his final will. Martin was there, present for the signing, the ink drying under his gaze.

The Comforting Lie is often the most effective weapon. After the will was sealed, life went on as before, a deceptive calm before a manufactured storm. Chris, who had been actively working on the Arkansas properties, remained in regular contact with Martin. They spoke of how things would be divided, how settlements might be apportioned. Martin negotiated in good faith — or so it seemed. What Chris did not know was that the will had already been signed, the decisions made. Martin knew exactly what was in it — knew the terms, the beneficiaries, the power it granted him. Yet when Chris asked directly about the will’s specifics, seeking clarity and reassurance, Martin would deflect. “I’m not sure what’s in it,” he would say, his tone carefully neutral, his gaze unwavering. “We’ll have to see what the lawyers say.” It was a performance, and Martin played it with the patience of a man who could wait years for the harvest of his deception.

The Nature of Betrayal, as Steinbeck wrote in East of Eden, suggests that the sins of Cain are not gone from the world; they are only repainted for each generation. In Cain’s time, the weapon was a stone in a field. In Martin’s, it was a pen and a lie repeated often enough to become the truth in his own mind. The betrayal here was not merely in the will — it was in the way Martin befriended Christine, after never having the slightest interest in her. Barry, consumed by his own pursuits and never one for intricate planning, said he remained largely oblivious to the subtle machinations unfolding around him, content in his assumption that his elder son status would guarantee him a significant share. Barry lied too but he was good at that.

The Final Months saw Dennis’s health decline, and the family dynamics shifted again, a morbid dance around the inevitable. Barry, once distant, began to circle back — not out of newfound affection for the ailing man he’d largely ignored, but because age and mortality have a way of sharpening one’s interest in what will be left behind. His visits were marked by awkward pleasantries and thinly veiled inquiries about his father’s affairs. Chris kept at the Arkansas properties, diligently working despite the distance, unaware she was toiling under a false premise, her efforts unknowingly benefiting the architect of her future disappointment. Martin, meanwhile, continued to play his role with chilling precision.

He was the dutiful son, the helpful brother, the man who would “make sure things were fair” when the time came. His voice was calm, his reassurances frequent, a soothing balm that masked the venom beneath. But the truth, like a splinter under the skin, was working its way toward the surface, causing unseen inflammation and festering resentment in those who were being deceived.

The Revelation arrived with the reading of the will, which became the stage for a deeply personal and devastating betrayal. Chris did not return to England for the will reading or the funeral. When she called Martin days after Dennis’s death, asking if the will had been opened, his response was a cold, cruel confirmation of her worst fears. “No,” he said, “but you’re not in it.” Shocked, she asked him how he knew. “Because I was there when Dad wrote it and signed it,” he replied, his admission a final, brutal blow. When the pieces finally locked into place, Chris saw at last the staggering scope of what Martin had done — not in haste, not in the heat of anger, but with years of deliberate planning and calculated deception.

He had positioned himself as the sole executor. He had been present at the signing in January 2017, a silent witness to the disinheritance of his own sister. He had kept Chris working on properties whose fate had already been decided, exploiting her dedication and trust from across an ocean. And all the while, he had lied, his denials echoing in her memory with the clarity of a struck bell. The shock was not merely in the contents of the will alone, but in the cold, dawning realization that every conversation, every promise, every seemingly innocuous negotiation had been a carefully placed thread in the intricate web of his deceit.

But Martin’s betrayal went deeper still. In 2011, Chris had bought a house with Dennis in America. Because Dennis had initially paid for it, the title was in his name, but Chris had subsequently paid back $46,000 of the $90,000 purchase price, with plans to pay the rest. Dennis had intended to write a will in the US, but after a visit in 2015 where he had an accident and decided to delay writing the will until his next visit, Martin had prevented him from ever returning.

Chris, holding a power of attorney over all of Dennis’s assets in the US, had a temporary shield. Martin, however, was patient; he knew the power of attorney would expire upon Dennis’s death. As there was no will in the US, the UK will, which Martin controlled, was the only document the courts would accept. Until Dennis’s death, Chris had no reason to distrust Martin or Barry, but the moment of his death changed everything. Martin sued Chris for her property, and after a grueling four-year legal battle, a battle that bled Chris financially and emotionally, she was evicted from her home by an armed sheriff. The betrayal was complete.

Lessons in the Ashes are the bitter fruit of betrayal. Family betrayal is an old story. It is older than the written word, older than the myths of Cain and Abel, older than the stones of any temple. But each time it happens, it is new for the ones living it, a fresh wound that cuts deeper than any other. Chris’s lesson, the one she hoped others would heed — is that trust within a family, the very foundation of belonging, can sometimes be the most dangerous trust of all. When betrayal comes from a stranger, it wounds the wallet or the pride. When it comes from a sibling, a person who shares your blood and history, it wounds the soul, leaving scars that may never fully heal.

Martin’s betrayal was not just about money or property; it was about control, about wielding power over his siblings, about rewriting the family’s narrative so that he, and he alone, would hold the pen, dictating who received what, and ultimately, who mattered. In the end, the will was more than a legal document; it was a monument to the slow, patient work of greed, a testament to the corrosive influence of envy that had festered for years. And for Chris, it was a stark reminder that vigilance is not cynicism — it is sometimes a necessary act of self-preservation, a shield against the darkness that can reside even within those closest to us. Because in every family, somewhere, the long shadow of Cain still lingers.

Barry, feigning ignorance to the deeper currents of manipulation that had secured his inheritance, continued his pursuit of fleeting pleasures, his sports cars and superficial relationships offering no lasting comfort. Martin, despite his newfound wealth, would find no true satisfaction. The act of betrayal would taint his victory, leaving him with a husk of a man, with hollow knowledge that his gain had come at the cost of his family’s unity and his own integrity.

Christine’s bitterness, though perhaps momentarily appeased by the inheritance, would soon return, for the money would not fill the void left by a lifetime of feeling like an outsider. She had achieved a financial victory, but at the cost of any genuine connection with her half-siblings.

Chris, though deeply hurt by the injustice and the loss of her home, found a different kind of solace. She understood that the true inheritance was not monetary, but the love and decency she had already given. She acknowledged the loss of her father and the fractured state of her family, but she refused to let the greed of others define her. She carried forward with her life, understanding that the real riches were those that could not be bought or stolen.

The Ely story has no heroic resolution, no redemption for those who chose greed over grace. Barry, Martin, and Christine lived outwardly full lives that were hollow at the core. Like the families in Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley, the Elys were shaped by their choices as much as by their circumstances. And like those in Dostoevsky’s Russia, they found that sin—once embraced—leaves a mark that no fortune can erase.

In the end, their tragedy was not that they had betrayed others, but that they had betrayed themselves. They had lived for the lust of money, and in doing so, had forfeited the only things worth having: family, loyalty, and love. It is a story as old as Cain and Abel, as familiar as the parable of the prodigal son—except here, the prodigal never returned, and the father’s blessing was stolen before it could be given. In the quiet corners of England, the brothers Ely remain a cautionary tale: that envy and greed, once they take root, will grow until they choke out every other thing worth having. Though they may enjoy their ill-gotten gains in this life, they will be judged—if not in this world, then in the next, and eternity is a very long time.

The Ely story has no heroic resolution, no redemption for those who chose greed over grace. Barry, Martin, and Christine lived outwardly full lives that were hollow at the core. Like the families in Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley, the Elys were shaped by their choices as much as by their circumstances. And like those in Dostoevsky’s Russia, they found that sin—once embraced—leaves a mark that no fortune can erase.

In the end, their tragedy was not that they had betrayed others, but that they had betrayed themselves. They had lived for the lust of money, and in doing so, had forfeited the only things worth having: family, loyalty, and love. It is a story as old as Cain and Abel, as familiar as the parable of the prodigal son—except here, the prodigal never returned, and the father’s blessing was stolen before it could be given. In the quiet corners of England, the brothers Ely remain a cautionary tale: that envy and greed, once they take root, will grow until they choke out every other thing worth having. Though they may enjoy their ill-gotten gains in this life, they will be judged—if not in this world, then in the next, and eternity is a very long time.